Kotlin is a general purpose, free, open source, statically typed “pragmatic” programming language initially designed for the JVM (Java Virtual Machine) and Android, and combines object-oriented and functional programming features. It is focused on interoperability, safety, clarity, and tooling support. Versions of Kotlin targeting JavaScript ES5.1 and native code (using LLVM) for a number of processors are in production as well.

Kotlin originated at JetBrains, the company behind IntelliJ IDEA, in 2010, and has been open source since 2012. The Kotlin project on GitHub has more than 770 contributors; while the majority of the team works at JetBrains, there have been nearly 100 external contributors to the Kotlin project. JetBrains uses Kotlin in many of its products including its flagship IntelliJ IDEA.

IDG

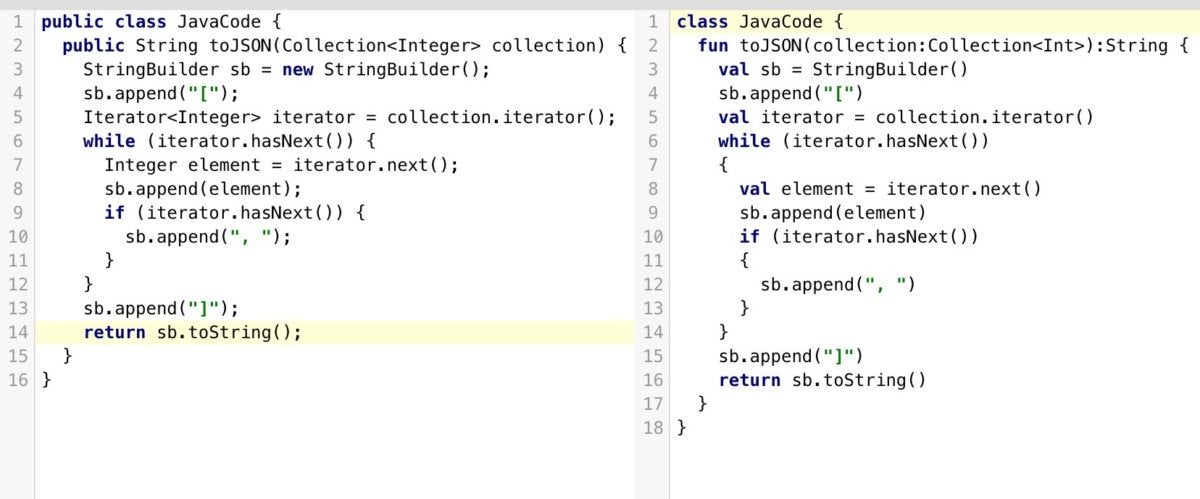

IDGKotlin as a more concise Java language

At first glance, Kotlin looks like a more concise and streamlined version of Java. Consider the screenshot above, where I have converted a Java code sample (at left) to Kotlin automatically. Notice that the mindless repetition inherent in instantiating Java variables has gone away. The Java idiom

StringBuilder sb = new StringBuilder();

Becomes in Kotlin

val sb = StringBuilder()

You can see that functions are defined with the fun keyword, and that semicolons are now optional when newlines are present. The val keyword declares a read-only property or local variable. Similarly, the var keyword declares a mutable property or local variable.

Nevertheless, Kotlin is strongly typed. The val and var keywords can be used only when the type can be inferred. Otherwise you need to declare the type. Type inference seems to be improving with each release of Kotlin.

Have a look at the function declaration near the top of both panes. The return type in Java precedes the prototype, but in Kotlin it succeeds the prototype, demarcated with a colon as in Pascal.

It is not completely obvious from this example, but Kotlin has relaxed Java’s requirement that functions be class members. In Kotlin, functions may be declared at top level in a file, locally inside other functions, as a member function inside a class or object, and as an extension function. Extension functions provide the C#-like ability to extend a class with new functionality without having to inherit from the class or use any type of design pattern such as Decorator.

For Groovy fans, Kotlin implements builders; in fact, Kotlin builders can be type checked. Kotlin supports delegated properties, which can be used to implement lazy properties, observable properties, vetoable properties, and mapped properties.

Many asynchronous mechanisms available in other languages can be implemented as libraries using Kotlin coroutines. This includes async/await from C# and ECMAScript, channels and select from Go, and generators/yield from C# and Python.

Functional programming in Kotlin

Allowing top-level functions is just the beginning of the functional programming story for Kotlin. The language also supports higher-order functions, anonymous functions, lambdas, inline functions, closures, tail recursion, and generics. In other words, Kotlin has all of the features and advantages of a functional language. For example, consider the following functional Kotlin idioms.

Filtering a list in Kotlin

val positives = list.filter { x -> x > 0 }For an even shorter expression, use it when there is only a single parameter in the lambda function:

val positives = list.filter { it > 0 }Traversing a map/list of pairs in Kotlin

for ((k, v) in map) { println(“$k -> $v”) }k and v can be called anything.

Using ranges in Kotlin

for (i in 1..100) { ... } // closed range: includes 100

for (i in 1 until 100) { ... } // half-open range: does not include 100

for (x in 2..10 step 2) { ... }

for (x in 10 downTo 1) { ... }

if (x in 1..10) { ... }The above examples show the for keyword as well as the use of ranges.

Even though Kotlin is a full-fledged functional programming language, it preserves most of the object-oriented nature of Java as an alternative programming style, which is very handy when converting existing Java code. Kotlin has classes with constructors, along with nested, inner, and anonymous inner classes, and it has interfaces like Java 8. Kotlin does not have a new keyword. To create a class instance, call the constructor just like a regular function. We saw that in the screenshot above.

Kotlin has single inheritance from a named superclass, and all Kotlin classes have a default superclass Any, which is not the same as the Java base class java.lang.Object. Any contains only three predefined member functions: equals(), hashCode(), and toString().

Kotlin classes have to be marked with the open keyword in order to allow other classes to inherit from them; Java classes are kind of the opposite, as they are inheritable unless marked with the final keyword. To override a superclass method, the method itself must be marked open, and the subclass method must be marked override. This is all of a piece with Kotlin’s philosophy of making things explicit rather than relying on defaults. In this particular case, I can see where Kotlin’s way of explicitly marking base class members as open for inheritance and derived class members as overrides avoids several kinds of common Java errors.

Safety features in Kotlin

Speaking of avoiding common errors, Kotlin was designed to eliminate the danger of null pointer references and streamline the handling of null values. It does this by making a null illegal for standard types, adding nullable types, and implementing shortcut notations to handle tests for null.

For example, a regular variable of type String cannot hold null:

var a: String = "abc"

a = null // compilation error

If you need to allow nulls, for example to hold SQL query results, you can declare a nullable type by appending a question mark to the type, e.g. String?.

var b: String? ="abc"

b = null // ok

The protections go a little further. You can use a non-nullable type with impunity, but you have to test a nullable type for null values before using it.

To avoid the verbose grammar normally needed for null testing, Kotlin introduces a safe call, written ?.. For example, b?.length returns b.length if b is not null, and null otherwise. The type of this expression is Int?.

In other words, b?.length is a shortcut for if (b != null) b.length else null. This syntax chains nicely, eliminating quite a lot of prolix logic, especially when an object is populated from a series of database queries, any of which might fail. For instance, bob?.department?.head?.name would return the name of Bob’s department head if Bob, the department, and the department head are all non-null.

To perform a certain operation only for non-null values, you can use the safe call operator ?. together with let:

val listWithNulls: List<String?> = listOf("A", null)

for (item in listWithNulls) {

item?.let { println(it) } // prints A and ignores null }Often you want to return a valid but special value from a nullable expression, usually so that you can save it into a non-nullable type. There’s a special syntax for this called the Elvis operator (I kid you not), written ?:.

val l = b?.length ?: -1

is the equivalent of

val l: Int = if (b != null) b.length else -1

In the same vein, Kotlin omits Java’s checked exceptions, which are throwable conditions that must be caught. For example, the JDK signature

Appendable append(CharSequence csq) throws IOException;

requires you to catch IOException every time you call an append method:

try {

log.append(message)

}

catch (IOException e) {

// Do something with the exception

}The designers of Java thought this was a good idea, and it was a net win for toy programs, as long as the programmers implemented something sensible in the catch clause. All too often in large Java programs, however, you see code in which the mandatory catch clause contains nothing but a comment: //todo: handle this. This doesn’t help anyone, and checked exceptions turned out to be a net loss for large programs.

Kotlin coroutines

Coroutines in Kotlin are essentially lightweight threads. You start them with the launch coroutine builder in the context of some CoroutineScope. One of the most useful coroutine scopes is runBlocking{}, which applies to the scope of its code block.

import kotlinx.coroutines.*

fun main() = runBlocking { // this: CoroutineScope

launch { // launch a new coroutine in the scope of runBlocking

delay(1000L) // non-blocking delay for 1 second

println("World!")

}

println("Hello,")

}

This code produces the following output, with a one-second delay between lines:

Hello,

World!

Kotlin for Android

Up until May 2017, the only officially supported programming languages for Android were Java and C++. Google announced official support for Kotlin on Android at Google I/O 2017, and starting with Android Studio 3.0 Kotlin is built into the Android development toolset. Kotlin can be added to earlier versions of Android Studio with a plug-in.

Kotlin compiles to the same byte code as Java, interoperates with Java classes in natural ways, and shares its tooling with Java. Because there is no overhead for calling back and forth between Kotlin and Java, adding Kotlin incrementally to an Android app currently in Java makes perfect sense. The few cases where the interoperability between Kotlin and Java code lacks grace, such as Java set-only properties, are rarely encountered and easily fixed.

Pinterest was the poster child for Android apps written in Kotlin as early as November 2016, and it was mentioned prominently at Google I/O 2017 as part of the Kotlin announcement. In addition, the Kotlin team likes to cite the Evernote, Trello, Gradle, Corda, Spring, and Coursera apps for Android.

Kotlin vs. Java

The question of whether to choose Kotlin or Java for new development has been coming up a lot in the Android community since the Google I/O announcement, although people were already asking the question in February 2016 when Kotlin 1.0 shipped. The short answer is that Kotlin code is safer and more concise than Java code, and that Kotlin and Java files can coexist in Android apps, so that Kotlin is not only useful for new apps, but also for expanding existing Java apps.

The only cogent argument I have seen for choosing Java over Kotlin would be for the case of complete Android development newbies. For them, there might be a barrier to surmount given that, historically, most Android documentation and examples are in Java. On the other hand, converting Java to Kotlin in Android Studio is a simple matter of pasting the Java code into a Kotlin file. In 2022, six years after Kotlin 1.0, I’m not sure this documentation or example barrier still exists in any significant way.

For almost anyone doing Android development, the advantages of Kotlin are compelling. The typical time quoted for a Java developer to learn Kotlin is a few hours—a small price to pay to eliminate null reference errors, enable extension functions, support functional programming, and add coroutines. The typical rough estimate indicates approximately a 40% cut in the number of lines of code from Java to Kotlin.

Kotlin vs. Scala

The question of whether to choose Kotlin or Scala doesn’t come up often in the Android community. If you look at GitHub (as of October 2022) and search for Android repositories, you’ll find about 50,000 that use Java, 24,000 that use Kotlin, and (ahem) 73 that use Scala. Yes, it’s possible to write Android applications in Scala, but few developers bother.

In other environments, the situation is different. For example, Apache Spark is mostly written in Scala, and big data applications for Spark are often written in Scala.

In many ways both Scala and Kotlin represent the fusion of object-oriented programming, as exemplified by Java, with functional programming. The two languages share many concepts and notations, such as immutable declarations using val and mutable declarations using var, but differ slightly on others, such as where to put the arrow when declaring a lambda function, and whether to use a single arrow or a double arrow. The Kotlin data class maps to the Scala case class.

Kotlin defines nullable variables in a way that is similar to Groovy, C#, and F#; most people get it quickly. Scala, on the other hand, defines nullable variables using the Option monad, which can be so forbidding that some authors seem to think that Scala doesn’t have null safety.

One clear deficit of Scala is that its compile times tend to be long, something that is most obvious when you’re building a large body of Scala, such as the Spark repository, from source. Kotlin, on the other hand, was designed to compile quickly in the most frequent software development scenarios, and in fact often compiles faster than Java code.

Kotlin interoperability with Java

At this point you may be wondering how Kotlin handles the results of Java interoperability calls, given the differences in null handling and checked exceptions. Kotlin silently and reliably infers what is called a “platform type” that behaves exactly like a Java type, meaning that is nullable but can generate null-pointer exceptions. Kotlin may also inject an assertion into the code at compile time to avoid triggering an actual null pointer exception. There’s no explicit language notation for a platform type, but in the event Kotlin has to report a platform type, such as in an error message, it appends ! to the type.